Introduction

Advantages of Laser Cutting Nickel Alloy

High Precision and Accuracy

Laser cutting offers exceptional precision, ensuring tight tolerances and consistent dimensions when cutting nickel alloys. This high level of accuracy is essential for components used in industries like aerospace, where precision is critical for performance and safety.

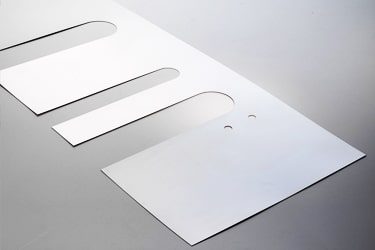

Clean and Smooth Edges

The laser cutting process produces clean, smooth edges with minimal burrs or oxidation, reducing the need for additional finishing. This feature is particularly beneficial when working with nickel alloys, which are often used in applications requiring corrosion-resistant, smooth surfaces.

Minimal Heat-Affected Zone

Laser cutting minimizes the heat-affected zone (HAZ), which helps preserve the material's integrity, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance. This is especially important for nickel alloys, as excessive heat can compromise their performance in extreme environments.

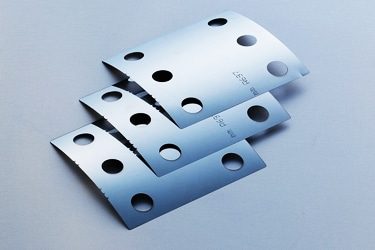

Ability to Cut Complex Shapes

Laser cutting allows for the production of intricate and complex geometries in nickel alloys. The high flexibility of the process enables the creation of detailed features such as small holes, curves, and fine patterns, ideal for specialized applications.

Reduced Material Waste

The narrow kerf produced by laser cutting results in minimal material loss, maximizing material usage. This efficiency helps reduce costs and supports environmentally sustainable practices by lowering scrap and waste when processing expensive nickel alloys.

Faster Production and Efficiency

Laser cutting is a fast process that allows for high-speed cutting of nickel alloys, even for thick materials. The automation capabilities and ease of setup make it ideal for both small-batch and high-volume production, improving overall manufacturing efficiency.

Compatible Materials

- Inconel 600

- Inconel 625

- Inconel 718

- Inconel 725

- Incoloy 800

- Incoloy 800H

- Incoloy 825

- Hastelloy C-276

- Hastelloy C-22

- Monel 400

- Monel K-500

- Nickel 200

- Nickel 201

- Nickel 205

- Nickel 300

- Nickel 400

- Nickel 600

- Nickel 800

- Nickel 900

- Nickel-Copper Alloy 400

- Nickel-Copper Alloy 405

- Nickel-Chromium Alloy 825

- Nickel-Chromium-Molybdenum Alloy 625

- Nickel-Chromium Alloy 600

- Alloy 400

- Alloy 600

- Alloy 625

- Superalloy 718

- Nickel-Based Alloy B-3

- Alloy X-750

- Nickel-Based Alloy K-500

- C-22

- Nimonic 90

- Nimonic 105

- Haynes 25

- Haynes 230

- Hastelloy X

- Waspaloy

- Rene 41

- Alloy 2200

Laser Cutting Nickel Alloy VS Other Cutting Methods

| Comparison Item | Laser Cutting | Plasma Cutting | Waterjet Cutting | Flame Cutting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting Precision | Very high precision | Moderate to low | Very high precision | Low precision |

| Edge Quality | Smooth, clean, burr-free | Rough edges, dross | Smooth but slightly matte | Rough, oxidized edges |

| Heat-Affected Zone | Minimal | Large | None (cold cutting) | Very large |

| Cutting Speed | Fast, especially on thicker alloys | Moderate | Slow | Very slow |

| Material Thickness Range | Thin to medium thickness | Medium to thick materials | Thin to very thick materials | Thick materials only |

| Detail & Complexity | Excellent for fine details | Limited detail | Excellent for intricate cuts | Very limited |

| Kerf Width | Narrow | Wide | Moderate | Wide |

| Secondary Finishing | Minimal or none required | Often required | Rarely required | Always required |

| Suitability for Nickel Alloys | Excellent, minimal oxidation | Poor, oxidation likely | Excellent, no oxidation | Poor, oxidation and coating damage |

| Reflective Material Handling | Designed with reflection control | Poor for reflective materials | No reflection issues | Not applicable |

| Operating Cost | Moderate | Low | High | Low |

| Equipment Investment | Moderate to high | Low to moderate | High | Low |

| Automation Capability | Highly automated CNC | CNC capable | CNC capable | Mostly manual |

| Environmental Impact | Low emissions, clean process | High fumes and noise | Water and abrasive waste | High smoke and gases |

| Cutting Quality Consistency | Excellent for repeatability | Inconsistent quality | Very consistent | Inconsistent |

Laser Cutting Capacity For Nickel Alloy

| Laser Power | Thickness (mm) | Cutting Speed (m/min) | Focus Position (mm) | Cutting Height (mm) | Gas | Nozzle (mm) | Pressure (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1KW | 1 | 2.4-3.6 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 1.0-1.4 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 0.5-0.7 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 1.5KW | 1 | 3.0-4.5 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 1.2-1.8 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 0.6-0.9 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 0.4-0.6 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 2KW | 1 | 3.6-5.4 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 1.4-2.2 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 0.7-1.1 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 0.5-0.7 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 0.4-0.5 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 3KW | 1 | 4.8-7.2 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 1.9-2.9 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 1.0-1.4 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 0.6-1.0 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 0.5-0.7 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 0.-0.6 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4KW | 1 | 5.8-8.6 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 2.3-3.5 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 1.2-1.7 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 0.8-1.2 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 0.6-0.9 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 0.5-0.7 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 0.3-0.4 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 6KW | 1 | 7.2-10.8 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 2.9-4.3 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 1.4-2.2 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 1.0-1.4 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 0.7-1.1 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 0.6-0.9 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 0.4-0.5 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 10 | 0.2-0.4 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 12KW | 1 | 10.8-16.2 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 4.3-6.5 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 2.2-3.2 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 1.4-2.2 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 1.1-1.6 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 0.9-1.3 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 0.5-0.8 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 10 | 0.4-0.5 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 12 | 0.3-0.4 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 14 | 0.2-0.3 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 20KW | 1 | 15.6-23.4 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 6.2-9.3 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 3.1-4.7 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 2.1-3.1 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 1.6-2.3 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 1.2-1.9 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 0.8-1.1 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 10 | 0.5-0.8 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 12 | 0.4-0.5 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 14 | 0.23-0.4 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 16 | 0.2-0.3 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 18 | 0.15-0.2 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 30KW | 1 | 19.2-28.8 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 7.7-11.5 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 3.8-5.8 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 2.6-3.8 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 1.9-2.9 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 1.5-2.3 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 1.0-1.4 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 10 | 0.6-1.0 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 12 | 0.4-0.7 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 14 | 0.3-0.5 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 16 | 0.25-0.4 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 18 | 0.2-0.3 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 20 | 0.15-0.2 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 25 | 0.1-0.15 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 3 | 18 | |

| 40KW | 1 | 21.6-32.4 | 0 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 |

| 2 | 8.6-13.0 | -0.8 | 0.8 | N2 | 1.4 | 14 | |

| 3 | 4.3-6.5 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 4 | 2.9-4.3 | -1.2 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 5 | 2.2-3.2 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 6 | 1.7-2.6 | -1.8 | 0.6 | N2 | 1.8 | 16 | |

| 8 | 1.1-1.6 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 10 | 0.7-1.1 | -2.5 | 0.6 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 12 | 0.5-0.8 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.2 | 16 | |

| 14 | 0.4-0.5 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 16 | 0.3-0.4 | -3.2 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 18 | 0.2-0.3 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 20 | 0.15-0.25 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 2.6 | 18 | |

| 25 | 0.12-0.18 | -4 | 0.5 | N2 | 3 | 18 | |

| 30 | 0.09-0.13 | -5 | 0.5 | N2 | 3 | 20 |

Applications of Laser Cutting Nickel Alloy

Customer Testimonials

Related Resources

Understanding The Odors Associated With Laser Cutting

This article provides a comprehensive guide to laser cutting odors, explaining the causes of odors, material-specific odors, health risks, and practical strategies for effectively controlling odors and ensuring safer operation.

What Safety Measures Should Be Taken When Operating Laser Cutting Machines

This article teaches the basic safety measures for operating a laser cutting machine, including hazard awareness, engineering controls, PPE, fire prevention, ventilation, training, and emergency response drills.

Addressing the Challenges of Fiber Laser Cutting: Common Problems and Solutions

This article explores common challenges in fiber laser cutting, including material-related issues, machine performance, and operator-related problems, offering practical solutions to optimize cutting quality and efficiency.

Precautions for Operating Laser Cutting Machines

This article provides a detailed overview of basic precautions for operating laser cutting machines, covering safety risks, proper setup, operating guidelines, maintenance procedures, and emergency preparedness.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Nickel Alloys Affect Laser Cutting Efficiency?

- High Melting Temperature Increases Energy Demand: Nickel alloys generally have higher melting points than carbon or stainless steels. This means more laser energy is required to initiate and sustain cutting. As a result, cutting speeds are typically slower, and higher laser power is needed, directly reducing overall cutting efficiency.

- Low Thermal Conductivity Retains Heat: Unlike copper or aluminum, nickel alloys conduct heat relatively poorly. Heat tends to remain concentrated in the cutting zone, which can be beneficial for melting but also increases the size of the heat-affected zone. Excessive heat buildup may require slower speeds or pauses to maintain edge quality, limiting throughput.

- Strong and Tough Microstructure: Nickel alloys are designed for high strength and resistance to heat, corrosion, and wear. These same properties make the molten material more viscous and harder to eject from the kerf. Poor melt flow increases the likelihood of dross, burrs, and incomplete cuts, all of which reduce process efficiency and increase rework.

- Sensitivity to Assist Gas Selection: Nickel alloys are commonly cut with nitrogen to prevent oxidation and preserve corrosion resistance. While nitrogen produces clean edges, it does not add heat to the process. Without the exothermic benefit of oxygen, cutting relies entirely on laser power, further slowing cutting speed compared to oxygen-assisted steel cutting.

- Reflectivity and Absorption Behavior: Nickel alloys absorb laser energy better than copper but less efficiently than carbon steel. This moderate absorption requires precise focus and parameter tuning. Poor absorption control can lead to unstable cutting, increasing downtime for adjustments, and reducing productive output.

- Increased Spatter and Fume Generation: Certain nickel alloys produce heavy metallic fumes and spatter during cutting. These byproducts can contaminate nozzles and optics, requiring more frequent cleaning and maintenance. Increased maintenance interruptions reduce effective cutting time and overall efficiency.

- Narrow Process Window: Nickel alloys often have a narrow range of acceptable cutting parameters. Small deviations in speed, power, or focus can cause defects such as rough edges or microcracks. Maintaining this tight control slows setup changes and limits flexibility in high-mix production environments.

- Thickness Limitations: As material thickness increases, efficiency drops sharply. Thick nickel alloys require significantly slower speeds and higher gas pressure to maintain cut quality, further reducing productivity.

Why Does Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys Produce Wider Heat-Affected Zones?

- High Melting Temperature Requires More Heat Input: Nickel alloys generally have higher melting points than carbon steel or aluminum. To achieve full penetration and stable cutting, the laser must deliver more energy over a longer duration. This increased heat input spreads beyond the immediate kerf, raising the temperature of surrounding material and expanding the HAZ.

- Low Thermal Conductivity Retains Heat: Nickel alloys conduct heat less efficiently than metals like copper or aluminum. Instead of dissipating heat quickly away from the cut zone, thermal energy remains concentrated near the cutting path. This heat retention causes adjacent material to stay hot for longer periods, enlarging the heat-affected zone.

- Slower Cutting Speeds Increase Thermal Exposure: To maintain cut quality and prevent defects such as incomplete cuts or excessive dross, nickel alloys are typically cut at slower speeds. Reduced travel speed means the laser dwells longer at each point along the cut, allowing more heat to accumulate and spread into the surrounding material.

- High Alloy Strength and Viscous Melt Behavior: Nickel alloys are engineered for strength and high-temperature performance. Their molten material tends to be more viscous and harder to eject from the kerf. This inefficiency in melt removal requires sustained laser energy, further increasing thermal exposure around the cut edge.

- Use of Inert Assist Gases: Nickel alloys are commonly cut with nitrogen to avoid oxidation and preserve corrosion resistance. Nitrogen does not contribute additional heat through chemical reactions, unlike oxygen-assisted cutting of carbon steel. As a result, higher laser power or longer exposure is required to maintain cutting, which expands the HAZ.

- Thicker Sections Amplify the Effect: As material thickness increases, more energy is needed to penetrate the full depth of the alloy. The additional heat required to cut thicker nickel alloys naturally increases the size of the heat-affected zone.

- Microstructural Sensitivity to Heat: Nickel alloys are sensitive to thermal cycles, and their microstructure can change significantly with prolonged heating. This makes the HAZ more visible and measurable compared to less heat-sensitive materials.

Why Do Nickel Alloys Cause Rapid Nozzle Wear?

- High Melting Temperature and Heat Intensity: Nickel alloys have high melting points, requiring greater laser power and longer exposure times to achieve a stable cut. This elevates temperatures around the cutting zone and nozzle tip. Prolonged exposure to high heat accelerates thermal fatigue, causing the nozzle material to soften, oxidize, or deform more quickly.

- Viscous and Heavy Molten Material: Molten nickel alloys are denser and more viscous than molten steel. Instead of flowing cleanly downward, the molten metal is more likely to splash or eject unevenly. This increases the amount of upward spatter striking the nozzle, leading to surface erosion and gradual distortion of the nozzle orifice.

- Increased Back Spatter and Rebound: Because melt ejection is less efficient, nickel alloys tend to produce more back spatter. High-energy droplets repeatedly impact the nozzle tip, causing micro-pitting and abrasion. Over time, this mechanical damage enlarges or irregularly shapes the nozzle opening, degrading gas flow symmetry.

- High-Pressure Assist Gas Effects: Nickel alloys are commonly cut using high-pressure nitrogen to maintain edge quality and prevent oxidation. The combination of high gas pressure and molten metal particles accelerates physical erosion at the nozzle edge. The gas stream can drive spatter particles into the nozzle surface with greater force, increasing wear rates.

- Extended Cutting Cycles: Laser cutting nickel alloys is typically slower than cutting mild steel. Longer dwell time means the nozzle remains exposed to heat, spatter, and reactive fumes for extended periods. This sustained exposure shortens nozzle lifespan even when cutting parameters are well optimized.

- Oxidation and Chemical Interaction: Although nitrogen is inert, trace oxygen and high temperatures can still promote surface oxidation of the nozzle material. Repeated heating and cooling cycles weaken protective coatings and base materials, making the nozzle more susceptible to erosion.

- Tight Process Windows and Sensitivity: Nickel alloys require precise focus height and nozzle alignment. Even minor misalignment increases spatter contact and uneven gas flow, which accelerates localized wear on one side of the nozzle.

Why Does Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys Produce Excessive Slag?

- High Melting Temperature and Energy Demand: Nickel alloys have higher melting points than carbon steel. Achieving and maintaining a fully molten cutting front requires higher laser power or longer exposure time. This sustained heating generates a larger volume of molten material, increasing the amount that must be removed during cutting and raising the risk of slag accumulation.

- Viscous Molten Metal Behavior: Molten nickel alloys tend to be thicker and more viscous than molten steel. This reduces flowability, making it harder for assist gas to blow the molten material cleanly out of the kerf. Instead of flowing downward smoothly, the molten metal clings to the cut edge and solidifies as slag.

- Low Thermal Conductivity Retains Heat: Nickel alloys conduct heat poorly compared to aluminum or copper. Heat remains concentrated near the cut zone, keeping molten material in a semi-liquid state longer. While this can aid melting, it also allows molten metal to adhere to the underside of the cut rather than being expelled efficiently.

- Slower Cutting Speeds Increase Slag Formation: To maintain cut stability and edge quality, nickel alloys are typically cut at slower speeds. Reduced travel speed increases laser dwell time, producing more molten metal per unit length. If assist gas flow is not perfectly optimized, excess molten material accumulates and solidifies as slag.

- Inert Assist Gas Limitations: Nickel alloys are usually cut with nitrogen to prevent oxidation and preserve material properties. Unlike oxygen-assisted cutting, nitrogen does not contribute additional heat through chemical reactions. As a result, all melting relies on laser energy alone, limiting the momentum available for ejecting molten metal and increasing slag risk.

- Thickness Effects: As nickel alloy thickness increases, the volume of molten material grows while gas access to the lower kerf becomes more restricted. This makes complete slag removal more difficult, especially at the bottom edge.

- Process Sensitivity: Nickel alloys have a narrow process window. Small deviations in focus height, nozzle alignment, gas pressure, or speed can dramatically reduce melt ejection efficiency, leading to rapid slag buildup.

- Impact on Post-Processing: Excessive slag often requires grinding or secondary finishing, increasing production time and cost.

Which Assist Gases Can Be Selected For Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys?

- Nitrogen (N2): Nitrogen is the most widely used assist gas for laser cutting nickel alloys. It is an inert gas that prevents oxidation during cutting, preserving the alloy’s corrosion resistance and surface finish. Nitrogen produces clean, bright cut edges with minimal discoloration, making it ideal for aerospace, chemical, and high-temperature applications. The drawback is that nitrogen does not contribute additional heat, so cutting speeds are slower and gas consumption is higher, especially for thicker materials.

- Oxygen (O2): Oxygen can be used for laser cutting certain nickel alloys in non-critical applications. It reacts exothermically with the molten metal, adding heat and increasing cutting speed. However, this oxidation damages the corrosion resistance of nickel alloys and creates oxide layers on the cut edge. For this reason, oxygen is generally avoided in precision or high-performance parts but may be acceptable where speed is prioritized over surface quality.

- Argon (Ar): Argon is another inert gas that can be used when extremely clean cutting conditions are required. It provides excellent oxidation prevention and is sometimes selected for highly sensitive nickel alloys. However, argon is more expensive than nitrogen and offers little practical advantage in most standard cutting scenarios, limiting its use to niche or research-based applications.

- Compressed Air: Compressed air contains oxygen and moisture, which promote oxidation and inconsistent cut quality. While it may be used for thin nickel alloys in low-cost, non-critical jobs, air cutting typically results in rough edges, increased slag, and reduced repeatability. It is rarely recommended for industrial nickel alloy processing.

- Impact on Slag and Edge Quality: Inert gases such as nitrogen and argon reduce slag adhesion and edge contamination. Oxygen-assisted cutting tends to increase slag formation and discoloration, requiring post-processing.

- Thickness Considerations: For thin to medium nickel alloy sheets, nitrogen provides the best balance of quality and control. For thicker sections, higher nitrogen pressure is required, which increases operating costs but maintains material integrity.

- Process Stability and Equipment Protection: Inert gases reduce spatter, fume formation, and contamination of optics and nozzles, helping stabilize the cutting process and extend maintenance intervals.

Why Does Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys Produce Excessive Spatter?

- High Melting Temperature and Sustained Heat Input: Nickel alloys have higher melting points than carbon or stainless steels. To initiate and maintain cutting, the laser must deliver higher energy or remain longer at the cut front. This sustained heat input generates larger volumes of molten metal, increasing the likelihood that droplets will be expelled violently rather than flowing smoothly out of the kerf.

- Viscous Molten Metal Behavior: Molten nickel alloys are denser and more viscous than molten steel. Instead of flowing freely downward under gravity and assisted by gas pressure, the melt resists movement and breaks away in irregular droplets. These droplets are easily ejected upward or sideways as spatter.

- Inefficient Melt Ejection: A clean cut depends on the assist gas efficiently removing molten material. In nickel alloys, melt ejection is less effective due to the combination of viscosity and high surface tension. When molten metal is not removed cleanly, pressure builds in the kerf, forcing droplets to escape unpredictably as spatter.

- Use of Inert Assist Gases: Nickel alloys are typically cut with nitrogen to prevent oxidation and preserve corrosion resistance. Nitrogen does not add heat through chemical reactions, unlike oxygen-assisted cutting. Without additional exothermic heat, the laser must work harder to maintain melting, often leading to unstable melt behavior and increased spatter.

- Slower Cutting Speeds Increase Exposure: To maintain edge quality and prevent incomplete cuts, nickel alloys are generally cut at slower speeds. Slower travel increases laser dwell time, producing more molten metal per unit length and giving spatter more opportunity to form and escape the kerf.

- Back Spatter from Kerf Instability: Fluctuations in melt pool stability can cause molten material to rebound upward toward the nozzle. This back spatter not only contaminates machine components but also contributes to the overall perception of excessive spatter during cutting.

- Thickness and Alloy Composition Effects: Thicker nickel alloys and certain compositions further worsen spatter by increasing molten volume and altering melt behavior. Minor differences in alloy chemistry can significantly affect spatter tendencies.

- Impact on Maintenance and Quality: Excessive spatter accelerates nozzle wear, increases optics contamination, and degrades edge quality, often requiring additional cleaning and maintenance.

Why Does Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys Result In Larger Tapers?

- High Melting Temperature Reduces Penetration Efficiency: Nickel alloys have higher melting points than most steels. While the laser easily melts the top surface where energy density is highest, maintaining sufficient heat at deeper levels of the cut is more difficult. As laser energy attenuates while traveling downward through the kerf, the lower portion receives less effective heat, resulting in narrower melting and increased taper.

- Viscous Molten Metal Restricts Downward Flow: Molten nickel alloys are thicker and more viscous than molten steel. This viscous melt does not flow downward smoothly under gravity and assist gas pressure. Instead, it clings to the kerf walls, especially near the bottom of the cut, limiting material removal and narrowing the kerf width at the exit side.

- Inefficient Assist Gas Penetration: Assist gas plays a key role in clearing molten material from the kerf. In thicker nickel alloys, gas flow struggles to reach the lower cutting zone with sufficient force. Reduced gas effectiveness at depth allows molten metal to partially re-solidify before full ejection, increasing taper formation.

- Slower Cutting Speeds Increase Heat Gradient: Nickel alloys are typically cut at slower speeds to ensure full penetration and acceptable edge quality. While slower speeds help maintain melting at the top, they also increase heat accumulation near the surface. This creates a stronger temperature gradient from top to bottom, exaggerating the difference in kerf width and resulting in larger tapers.

- Use of Inert Assist Gases: Nickel alloys are commonly cut with nitrogen to prevent oxidation. Nitrogen does not add heat through chemical reactions, unlike oxygen-assisted cutting of carbon steel. Without additional heat generation at the cut front, maintaining uniform melting throughout the thickness becomes more difficult, especially near the bottom of the kerf.

- Beam Focus and Divergence Effects: Laser beams naturally diverge beyond the focal point. Even with careful focus positioning, some divergence occurs as the beam travels downward. In nickel alloys, where cutting efficiency is already limited, this divergence further reduces energy density at the lower edge, contributing to taper.

- Thickness Sensitivity: As material thickness increases, all of these effects become more pronounced. Thicker nickel alloys consistently exhibit larger tapers unless compensated with higher power, optimized focus strategies, or multiple cutting passes.

Why Does Laser Cutting Of Nickel Alloys Lead To Edge Microcracks?

- High Melting Temperature and Thermal Stress: Nickel alloys have a higher melting point than many other metals, requiring more laser energy to melt the material. This increased heat input causes a significant temperature gradient between the cutting zone and the surrounding material. Rapid heating and cooling during the laser cutting process create thermal stress, which can lead to the formation of microcracks along the edge, especially in areas where the material undergoes rapid cooling.

- Material Toughness and Sensitivity to Thermal Cycling: Nickel alloys are engineered for strength and resistance to high temperatures, but this makes them more prone to brittle behavior under thermal stress. As the material cools rapidly after laser exposure, the difference in thermal expansion between the molten and solidified zones can result in internal stresses. These stresses, when combined with the material’s hardness, promote the formation of microcracks at the edge of the cut.

- Localized Cooling and Rapid Solidification: The laser cutting process generates intense heat at the cutting point, followed by rapid cooling. In nickel alloys, this rapid cooling can result in localized solidification, causing a mismatch in the microstructure along the cut edge. This difference in cooling rates can increase susceptibility to crack formation, as the material may not have time to form a uniform, stress-relieved structure.

- Oxidation and Surface Impurities: When laser cutting nickel alloys, especially in the presence of oxygen, surface oxidation can occur. The formation of brittle oxide layers on the cut edge can weaken the material and create a more likely site for cracks to form. The presence of impurities or uneven oxidation further exacerbates the issue, making the edge more susceptible to cracking.

- Inadequate Assist Gas Flow: Assist gases, such as nitrogen, are used to expel molten material from the kerf during cutting. If the assist gas pressure is insufficient or uneven, molten material may not be effectively removed, causing it to cool and solidify unevenly along the edge. This uneven cooling can induce stresses at the edge, leading to microcracks.

- Microstructural Changes During Cutting: Laser cutting can induce localized changes in the microstructure of the material, particularly in the heat-affected zone (HAZ). The cooling process after the laser cutting passes can cause the formation of hard, brittle phases that are more prone to cracking under mechanical stress or even thermal cycling during the cutting process.