What “Precision” Means for Oscillating Knife Cutting

Dimensional Accuracy

Repeatability

Resolution

Feature Precision

Edge Quality Precision

Registration Accuracy

Typical Precision Ranges

Typical Real-World Results

Why “Machine Spec Accuracy” Differs from “Cut Part Accuracy”

Materials Strongly Influence Achievable Tolerance

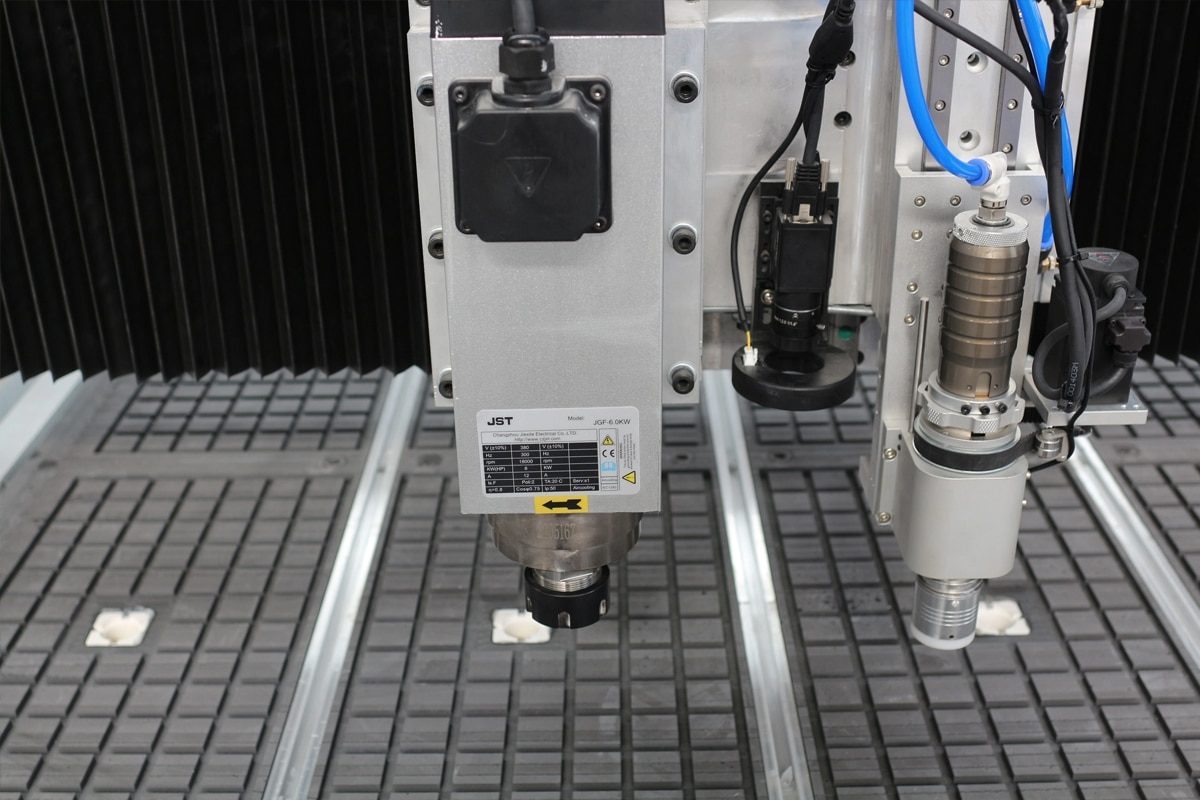

Anatomy of Oscillating Knife Cutting Machines and How Each Part Affects Precision

Frame and Gantry Stiffness

Linear Guides, Bearings, and Rails

Drive System

Motors and Control

Encoders and Feedback Location

Tool Head Mechanics

The Knife Itself

Blade Tip Geometry and Corner Fidelity

Blade tip geometry is the first “hard limit” on how sharp and detailed a cut can be. Even if your CAD file shows a perfect 90° internal corner, the blade cannot magically cut a corner sharper than its own effective cutting tip. The most important geometric factors are:

- Tip Radius/Point Sharpness: A needle-like tip can enter tight inside corners and small radii with minimal rounding. A blunter tip leaves a larger inside radius because it physically cannot reach into the corner without the side of the blade contacting first.

- Blade Thickness and Wedge Angle: Thicker blades and steeper bevels are tougher and last longer, but they displace more material. That displacement shows up as “corner blowout” in soft foam, slight corner bulging in rubber, or fraying in textiles.

- Single-Bevel vs Double-Bevel Behavior: Some blade grinds have a directional bias in how they push material. In delicate features (thin bridges, small notches), that bias can cause asymmetric distortion if feeds and turn strategies are aggressive.

- Penetration Dynamics: The tip doesn’t just slice; it pierces at the start of a cut and at sharp direction changes. In fibrous or layered materials, the piercing step can snag fibers or separate layers if the tip shape is not suited to the substrate.

Blade Offset and Tool Compensation

Why offset matters so much in oscillating knife cutting:

- Curves and Circles: If offset compensation is wrong, circles won’t truly be circles. You can see subtle size errors, flat spots, or geometry that “drifts” in one direction.

- Inside Features: Small holes and internal cutouts are especially sensitive. A tiny offset error becomes a large percentage of the feature size, so holes can come out undersized, out-of-round, or with visibly inconsistent radii.

- Corner Behavior: When the tool changes direction, the blade may not pivot instantaneously to the new orientation. Without correct compensation and a sensible corner strategy, inside corners gain unintended radii, and outside corners can “overcut” or appear slightly hooked.

Most professional systems address this with tool compensation—the software intentionally shifts the toolpath so the cut edge lands on the design line. For this to work, the machine must have:

- Correct blade parameters in the tool library (effective offset, blade type, cutting depth behavior).

- The right corner strategy (slowdown, micro-lead-in/lead-out, or corner looping, depending on material and detail needs).

- Consistent tool head alignment (if the blade is slightly tilted or has play, the effective offset changes during cutting).

Oscillation Frequency and Amplitude

Oscillation is the defining feature of these cutters: the blade moves up and down rapidly while traveling along X/Y. The goal is to turn dragging friction into repeated slicing, reducing force and making the cut cleaner. But frequency and amplitude are not just “quality settings”—they directly affect precision by changing the cutting forces acting on both the tool and the material.

- Oscillation Frequency (Strokes Per Minute/Second):

- Higher frequency generally lowers cutting resistance, helping the blade track the programmed path instead of pulling the material. This can improve dimensional accuracy in sticky, grippy materials like rubber or tacky foams.

- Too high, however, can introduce vibration in the tool head and gantry. Vibration can show up as tiny edge chatter, slight waviness in curves, or loss of fidelity in micro-features, particularly at high travel speeds.

- Oscillation Amplitude (Stroke Length):

- Low amplitude can struggle in thick, fibrous, or layered materials, leading to incomplete separation, tearing, or “hairy” edges. Those defects often get mistaken for bad positional accuracy.

- High amplitude can over-agitate soft materials, increasing local deformation. On very soft foam or stretchy textiles, you may see edges that look slightly “pulled” or corners that soften because the material is moving as it’s being cut.

- The Precision Trade-Off:

- For delicate features—small holes, tight inside corners, narrow bridges—operators often reduce travel speed, moderate oscillation, and prioritize controlled slicing over raw throughput. For long straight profiles in stable materials, higher speed and higher frequency can be used because feature fidelity is less sensitive.

Blade Sharpness and Wear

Blade wear rarely fails dramatically. Instead, it slowly steals precision while everything looks “mostly fine”—until parts stop fitting. As a blade dulls, three things happen that matter for precision:

- Cutting Force Rises: The machine must push harder to separate the material. Higher force increases material compression and increases blade deflection. Both effects alter final dimensions.

- Material Deformation Increases: Soft substrates compress before they cut. When they rebound after cutting, edges can shift, small features distort, and inside corners look rounded or “mushy.”

- Edge Quality Deteriorates: Fraying, fuzzing, tearing, delamination, and edge roll become more common. Even if dimensions measure close, poor edges can make parts functionally inaccurate (bad seals, weak tabs, poor bonding surfaces).

Wear affects different materials in different ways:

- Foam: Dull blades crush cells and pull rather than slice, causing edge compression and inconsistent thickness at the cut line.

- Textiles: You’ll see fiber pull-out, fuzz, and snagging—especially on tight curves and tiny holes.

- Rubber/Gaskets: Dullness can cause edge tearing, micro-cracks, and rough edges that compromise sealing performance.

- Corrugated/Fiber Board: Increased tearing and ragged edges appear, and small features lose definition fast.

Practical precision management usually includes:

- Scheduled blade replacement based on cut time, distance, or material type.

- Quick test cuts of a known geometry (circles, squares, notches) to spot drift early.

- Inspecting corners and small holes first—these fail before large outlines do.

Material Behavior

Stretch and Elastic Recovery

This effect is especially pronounced in:

- Long contours with minimal interruption

- Narrow bridges or thin features

- Curved paths where directional forces constantly change

- Materials with low modulus and high elasticity

Compression and Rebound (Foam, Felt, Gasket Materials)

Compression effects also influence feature fidelity:

- Small holes may partially close or ovalize after cutting

- Sharp inside corners may soften or round

- Edge thickness can vary along the cut path

Laminates and Adhesive-Backed Materials

Additional complications include:

- Adhesive softening due to frictional heat

- Adhesive buildup on the blade, increasing drag over time

- Differential compression between layers of varying stiffness

Corrugated Board and Honeycomb Structures

Precision challenges with these materials include:

- Waviness along long edges

- Tearing at flute transitions

- Inconsistent feature definition in small cutouts

- Directional sensitivity based on flute orientation

Rigid and Semi-Rigid Plastics

Common precision-related issues include:

- Edge chipping in brittle plastics

- Heat buildup is causing localized softening and edge deformation

- Blade deflection due to higher cutting forces

- Stress whitening or micro-cracks at tight corners

Vacuum Hold-Down and Fixturing

Vacuum Zone Design and Leakage

Most flatbed oscillating knife cutting machines rely on a vacuum pump feeding a segmented (zoned) cutting bed. The idea is simple: concentrate suction where the material is, reduce suction where it isn’t, and maintain a strong pressure differential that pins the sheet down. Precision depends on how effectively the system maintains that pressure differential during the entire cutting cycle—especially after the cut has created openings that invite air in.

- Why Zone Design Matters for Precision

- Local holding force, not total pump size, is what prevents slip. A powerful pump spread across a large open area can produce weak hold-down in the actual cut region. Smaller active zones increase the effective hold-down where the knife is working.

- Part location vs. active zones: If the material only partially covers a zone, uncovered areas become “open leaks” that bleed vacuum. That reduces holding force under the part and can lead to subtle shifts during cornering or while cutting tight curves.

- Dynamic leakage as you cut: Every through-cut creates a new path for air. Late in the job—after many features are cut—the sheet can lose sealing integrity and become more prone to micro-slippage. This is why parts cut early can measure “better” than parts cut late on the same sheet.

- Main Leakage Sources that Quietly Degrade Precision

- Unused zones left open: If zones that aren’t covered are still active, they behave like giant holes in the system. Masking or shutting off unused zones can dramatically increase effective hold-down.

- Porous materials acting like a sponge: Felt, many foams, and corrugated board allow airflow through the sheet. Vacuum still works, but the effective pressure under the material drops, and the sheet can “float” slightly during rapid tool motion unless zones are managed carefully.

- Bed surface wear and seal damage: Worn gaskets, warped zone dividers, clogged channels, or surface damage cause uneven suction distribution. The result is inconsistent precision across the bed—parts cut in one area are perfect, while the same geometry in another area is slightly off.

- Micro-leaks from debris: Dust, fibers, and offcuts prevent full contact between sheet and bed. Even tiny debris can create localized lift, which becomes a weak spot where the knife can catch and drag.

- Precision-Oriented Setup Practices

- Use the smallest practical active zone footprint for the job.

- Mask uncovered bed areas (common with smaller sheets) to reduce open leakage.

- When cutting porous materials, prioritize higher vacuum flow and better zone sealing, and consider sequencing high-precision features earlier while the sheet is still well sealed.

- Keep the bed clean—because precision is often lost one tiny crumb at a time.

Material Flatness Matters

Vacuum works only where there is real contact. If the sheet is curled, wavy, tensioned from being stored on a roll, or internally stressed, it may bridge over low areas instead of lying flat. That reduces holding force precisely where you need it most—near corners, small features, and thin webs.

- How Flatness Directly Affects Dimensional Accuracy

- Lift creates a lever arm: When a sheet is lifted even slightly, the blade’s lateral force can move it more easily. What would have been a harmless force on a well-seated sheet becomes enough to cause creep.

- Vertical variation turns into lateral error: If the sheet rises, the blade enters at a slightly different effective angle or engages more of the bevel, increasing drag and shifting the cut edge. This is especially noticeable in thick foam, felt, and semi-rigid plastics.

- Inconsistent depth and resistance: A sheet that isn’t flat produces inconsistent penetration into the underlay. That changes cutting resistance from one section to another, leading to local distortions—one corner is crisp, another looks slightly rounded or torn.

- Common Flatness Problems and their Precision Symptoms

- Rolled stock “memory”: Curl causes the edges to lift, which is exactly where many nests place parts. Lifted edges often produce inaccurate perimeters and poor registration.

- Warped sheets: Bowed plastics can rock or settle during cutting as stresses release, changing cut accuracy mid-job.

- Uneven thickness or density: Some foams and felts vary across the sheet; vacuum may hold some regions tightly and others less so, causing region-to-region tolerance variation.

- Ways Shops Improve Flatness for Better Precision

- Pre-conditioning: Allow rolled materials to relax, unroll in advance, or apply gentle reverse curl when appropriate.

- Better contact: Use an underlay that helps the sheet “seat,” and increase the vacuum where the sheet tends to lift.

- Hybrid fixturing: For stubborn materials, combine vacuum with edge clamping, temporary weights outside the cut area, or tabs/bridges in the toolpath to keep parts stable until the end.

Underlay/Sacrificial Layer Choice

The underlay is often treated like a consumable protective surface, but in precision terms, it’s also a mechanical interface and a vacuum interface. It affects how evenly suction is distributed, how well small features are supported, and how consistent the blade’s effective cutting depth remains across the bed.

- How the Underlay Choice Changes Precision

- Vacuum distribution: A permeable underlay helps spread suction evenly and can improve hold-down for porous materials and small parts. A more sealed surface can increase peak suction for non-porous sheets but may create “hot spots” and dead zones if airflow paths are limited.

- Support under the cut: Small holes, narrow slots, and tight notches are prone to distortion if the material flexes downward during penetration. A supportive underlay reduces deflection and preserves feature geometry.

- Depth consistency and drag control: The blade typically cuts slightly into the underlay. If the underlay is too hard, the blade experiences higher resistance and increased wear; if it’s too soft, the blade can sink deeper, increasing drag and causing dimensional drift—especially on fine features and curves.

- Bed wear patterns create precision drift: Over time, grooves, compressed regions, and embedded debris create uneven support and uneven vacuum sealing. You may see the same geometry cut differently depending on where it sits on the bed.

- Underlay-Related Precision Best Practices

- Replace or resurface underlays before grooves and compression become severe—precision losses can be gradual and easy to miss until parts fail fit checks.

- Match underlay type to material: what helps vinyl lay flat may be a poor choice for thick foam or corrugated board.

- Watch for feature-specific failures (small holes not clean, corners rounding, incomplete separation) as early indicators that underlay support or depth control needs attention.

Motion Control and Cutting Strategy

Acceleration, Jerk, and Corner Behavior

Most precision problems show up first at corners, and the reason is physics. When the tool is moving fast and must change direction, the machine has to manage inertia and cutting resistance simultaneously. The key motion terms are:

- Acceleration: How quickly the machine ramps up and slows down.

- Jerk: How abruptly acceleration changes (the “snap” of motion).

- Cornering Strategy: How the controller negotiates direction changes—slowdown, rounding, stop-and-go, or smoothed blending.

What Goes Wrong When Acceleration and Jerk Are Too Aggressive

- Corner Rounding: The controller may intentionally smooth the path to maintain speed. That produces corners that look “melted” compared to the CAD line—especially on small internal corners where the allowed rounding radius becomes a large fraction of the feature.

- Overshoot and Hooks: If the axis cannot decelerate and reverse cleanly, the tool can slightly overshoot the corner and then correct, leaving a tiny hook or bulge at the exit. This is common when cutting dense rubber, thick foam, or semi-rigid plastics that increase lateral tool load.

- Blade Lag and Holder Compliance: The oscillating knife holder has its own stiffness limits. When the gantry changes direction quickly, the blade may lag a fraction of a millimeter behind the commanded path, then catch up—an effect that is subtle but measurable on tight features.

- Vibration-Induced Edge Waviness: High jerk excites vibration in the gantry and tool head. That can show up as chatter-like texture on curved edges and inconsistent corner sharpness.

Precision-Minded Tuning Concepts

- Use lower jerk / smoother S-curve acceleration profiles for jobs with tight corners or small features.

- Apply corner slowdowns or feature-based speed control (fast on long straight runs, slower on small radii and notches).

- Be cautious with “constant velocity” modes that prioritize speed over exact cornering; they can be excellent for signage or packaging, but risky for gasket-grade tolerances.

Path Planning

Path planning is one of the most underappreciated precision levers because it controls how stable the material remains during critical cuts.

- Inside-Out Cutting (Internal Features First)

- Cutting holes, slots, notches, and internal contours while the sheet is still one solid piece maximizes stability.

- Vacuum hold-down remains strongest because the sheet is not yet perforated into islands.

- Internal features are less likely to distort because the surrounding material supports them during cutting.

- Outside-in Cutting (Outer Contour First)

- Once the perimeter is cut, the part becomes an “island.” Even with a vacuum, the seal often weakens because air can leak around the cut edges.

- The part may shift minutely during later internal cuts, especially in porous materials, stretchy sheets, or thick foams.

- Small features may lose fidelity because the part can lift or rotate slightly during direction changes.

- Best-Practice Strategy for Precision

- Cut inside-out whenever internal feature accuracy matters.

- Add tabs/bridges (small uncut connections) to keep the part anchored until the end—especially for small parts or thin webs.

- Sequence cuts so high-precision features happen early, while the sheet is least perforated, and vacuum sealing is best.

Lead-Ins, Lead-Outs, and Seam Placement

Every closed contour has a start/stop, and that creates a seam. Seams are unavoidable—but how you manage them determines whether they are invisible or become a measurable defect.

- Lead-Ins and Lead-Outs

- A lead-in lets the blade “settle” into steady cutting before it reaches the true boundary. This reduces start-point gouges, tiny notches, and edge tearing.

- A lead-out lets the cut exit smoothly instead of stopping abruptly on a critical edge.

- Why Seams Affect Precision

- The start/stop region often has a slight mismatch from blade dynamics: brief dwell, tool orientation settling, or oscillation behavior changing at the beginning/end.

- On compressible materials, a micro-dwell can compress the edge, shifting the cut line.

- On adhesive-backed laminates, the seam area may show extra drag or adhesive buildup effects.

- Seam Placement Strategies

- Place seams on non-critical edges, straight sections, or areas that won’t mate with another part.

- Avoid seams at tight corners, thin tabs, or small holes, where a tiny mark becomes functionally significant.

- For aesthetic products, hide seams under a fold, label, or assembly overlap when possible.

Multi-Pass Cutting for Thick or Tough Materials

One of the biggest myths is that a “stronger” single pass always improves precision. In reality, a heavy single pass often increases force, drag, and material distortion—especially with thick foams, dense gasket rubber, multilayer laminates, and semi-rigid plastics.

- How Multi-Pass Improves Precision

- Lower Peak Cutting Force: Each pass removes less material resistance, reducing lateral drag that can pull the sheet or deflect the blade.

- Reduced Compression and Rebound: Especially in foam and felt, a deep single pass compresses heavily; staged passes slice more cleanly with less deformation.

- Cleaner FeatureFidelity: Small holes and notches are less likely to tear or ovalize when the blade isn’t fighting maximum resistance in one go.

- Better Edge Quality: Progressive cutting often reduces edge roll in rubber and reduces delamination in laminates.

- Common Multi-Pass Approaches

- Depth Stepping: Several passes, each deeper than the last, until full separation is achieved.

- Rough + Finish: A first pass close to full depth, followed by a lighter finishing pass to clean fibers and improve edge definition (useful for composites or fibrous board).

- Adaptive Pass Count: More passes for tight radii and small features, fewer for long straight edges to balance speed and accuracy.

Tool Pressure and Depth Control

Tool pressure and depth control determine how the blade engages the material and underlay, which directly affects dimensional accuracy, corner fidelity, and edge cleanliness.

- Too Much Pressure/Too Deep

- Increases compression (foam, felt) and stretch (rubber, textiles).

- Increases drag, raising the chance of micro-slip and feature distortion.

- Accelerates blade wear, which then increases force even more—a feedback loop that slowly widens tolerances.

- Can cause overcut into the underlay, changing effective blade engagement and making small features less consistent.

- Too Little Pressure/Too Shallow

- Causes incomplete cuts, hanging chads in small holes, or fibers that don’t separate cleanly.

- Forces operators to rerun passes inconsistently, reducing repeatability.

- Depth Consistency is System Problems: Even if the tool depth is set correctly, the real depth varies with:

- Material thickness variation across the sheet

- Bed flatness and underlay wear

- Vacuum seating quality (a sheet that lifts changes the effective depth)

- Tool Holder Compliance

Programming-to-Cut Precision

Registration Workflow

A detailed, real-world registration workflow typically includes the following stages. Each stage reduces uncertainty, and skipping steps often shows up as “mysterious” misalignment later.

- File Preparation and Coordinate Integrity

- Confirm the file scale and units (mm vs inch errors are a classic “registration” disaster).

- Ensure the geometry is clean: closed contours are truly closed, layers are assigned correctly, and offsets/tool compensation match the chosen blade.

- If print-to-cut, confirm that registration marks (fiducials) are generated correctly and placed where they will remain visible and stable.

- Material Loading and Physical Referencing

- Establish a repeatable physical reference: corner stops, edge guides, alignment pins, or a consistent squaring method.

- Apply vacuum/fixturing and let the sheet settle. Some materials relax after a vacuum is applied; if you register too early, your “truth” changes mid-job.

- For rolled materials, manage curl and tension. A sheet that is still fighting to flatten will drift or skew as it relaxes.

- Mark Detection or Feature Detection

- Fiducial-based vision: Cameras locate printed registration marks. The system measures their actual position relative to the machine’s coordinate frame.

- Contour/edge detection: Some systems can detect the printed contour or edge features directly, useful when fiducials are not available.

- Mechanical probing: For non-printed materials, a probe can locate physical holes, edges, or punched features and establish the datum from the part itself.

- Detection quality depends on contrast, lighting, lens calibration, focus, cleanliness, and mark design.

- Compute Alignment Transforms

- Translation (X/Y shift): Corrects a simple offset from the loading position.

- Rotation (skew correction): Corrects a sheet that is not square to the bed.

- Scale correction (uniform): Corrects if the entire print or material is consistently larger/smaller than expected.

- Non-uniform transforms (warp/distortion): Corrects if the sheet is stretched more in one region than another.

- Apply Compensated Toolpath and Verify

- The controller modifies the cut path so the blade follows the corrected geometry.

- For high-value jobs, a “proof” action is common: cut a small test shape, run a dry-run, or verify alignment at multiple points across the sheet before committing.

The Biggest Threats to Registration Accuracy

Registration errors often come from predictable sources. Understanding them helps you prevent them rather than blaming the machine.

- Loading Skew and Squareness Errors

- A small skew at the edge becomes a large positional error across the sheet length.

- Large-format work is especially sensitive: the farther you cut from the reference edge, the bigger the offset becomes.

- Edge guides help, but if the material edge is not straight (common in textiles, foam, and some boards), “squaring” to the edge may actually introduce error.

- Material Movement After Registration

- Vacuum settling: The vacuum can pull a flexible sheet into better contact, slightly shifting it from the moment registration was measured.

- Creep during cutting: Oscillating knives generate lateral forces; porous materials and partially cut sheets can creep by fractions of a millimeter—enough to show up on printed graphics.

- Perforation leakage effects: As internal features are cut, vacuum effectiveness drops, and the sheet becomes easier to shift, particularly near the end of the job.

- Print-To-Cut Distortion

- Printing itself often introduces scale error and warping due to:

- Substrate tension and feed rollers

- Heat (especially with some ink/curing processes)

- Humidity changes between printing and cutting

- Laminate shrinkage or expansion

- The print may be perfect at the fiducials, but slightly distorted between them. A basic shift/rotate correction cannot fix that.

- Vision Detection Limitations

- Glossy laminates cause reflections; textured materials reduce contrast; inks can bleed; dust obscures marks.

- Poor lighting creates shadows or hotspots that shift detected mark centers.

- Camera calibration matters: lens distortion, improper focus, or incorrect camera-to-tool offset calibration will convert “good detection” into wrong correction.

- Small or poorly designed fiducials amplify error. A fuzzy mark edge produces inconsistent centroid detection.

- Human and Software Setup Mistakes

- Wrong tool selected in the CAM (incorrect blade offset), wrong layer cut order, or wrong origin choice.

- Import scaling issues, DPI assumptions for raster artwork, or incorrect nesting rotation.

- Fiducials are placed too close to edges (they may be cropped) or too close together (they don’t capture large-area distortion).

Distortion Compensation

- Multi-Point Registration (Beyond Two Marks)

- Using more than two fiducials allows the controller to detect not just rotation and translation, but also:

- Differential scaling (X scale differs from Y scale)

- Slight shear (parallelogram-like distortion)

- The more widely spaced the points, the better the system can “see” global distortion trends.

- Grid-Based Warping (Mapping the Sheet)

- For high-precision print-to-cut, systems may read a grid of marks across the sheet and build a distortion map.

- The software then warps the toolpath so it matches the printed reality locally, not just globally.

- This is particularly valuable for large prints, soft substrates, and laminated graphics where distortion varies across the area.

- Segment or Panel Compensation

- Instead of mapping the entire sheet, some workflows split large nests into panels, each with its own local registration. This reduces the impact of cumulative distortion and makes the correction more stable.

- Scale and Calibration Compensation

- If a printer consistently outputs at 100.2% in X and 99.8% in Y, applying a predictable scale correction can greatly improve cut alignment.

- This is often the simplest high-impact fix for recurring print-to-cut errors.

- Choosing What “Accuracy” Means

- Distortion compensation forces an important decision:

- Do you want the cut to match the nominal CAD dimensions, or to match the printed or distorted substrate?

- In packaging and signage, matching the print is often the priority. In gasket cutting, nominal dimensions may matter more than printed alignment. Some jobs require a compromise: hold critical dimensions while allowing minor print-following elsewhere.

How to Interpret Machine Specifications Without Getting Misled

Positioning Accuracy vs Cut Accuracy

A crucial distinction is positioning accuracy (sometimes called axis accuracy) versus cut accuracy (finished-part accuracy).

- What Does Positioning Accuracy Usually Means

- It describes how close the carriage or tool head can move to a commanded coordinate under test conditions.

- It is often measured with metrology tools (laser interferometers, dial indicators, or encoder readings) while the machine is not cutting, or while it is moving slowly and smoothly.

- It may be stated as a best-case number at a specific temperature, speed, and load—sometimes without clarifying those conditions.

- Why Positioning Accuracy is Not the Same as Cut Accuracy: Cut accuracy includes everything that happens when the blade interacts with real material:

- Blade deflection and holder compliance: The knife can bend or lag slightly when it meets resistance—especially in dense rubber, thick foam, or semi-rigid plastics.

- Material deformation: Foams compress and rebound; textiles and elastomers stretch and recover; corrugated structures resist unevenly. These behaviors shift the “true” cut edge even if the tool head is exactly where it should be.

- Dynamic motion effects: Corners, tight curves, and rapid direction changes introduce inertial forces that don’t exist in static accuracy tests.

- Hold-down variability: Vacuum leakage, part islands, and cut-through paths can allow micro-slip that the axis accuracy spec never accounts for.

- Tool compensation and calibration: Blade offset, camera-to-tool calibration (for print-to-cut), and depth control errors all change where the cut lands.

- How to Read a Spec Sheet Safely

- Treat positioning accuracy as an upper bound on what might be possible—not a guarantee of part tolerance.

- Look for language that indicates whether the number is axis positioning, repeatability, or cutting accuracy, and whether it was measured over a short stroke or the full travel.

- Ask for evidence of cut-part accuracy on representative materials, ideally with documented test geometry (circles, holes, corners, long runs) and stated cutting parameters.

Repeatability Matters More for Production

For production, repeatability (how consistently the machine returns to the same point and reproduces the same result) is often more valuable than chasing perfect absolute accuracy.

- Why Repeatability is the Production Hero

- Predictability enables compensation: If the machine consistently cuts 0.2 mm undersize on a particular foam due to compression, you can often compensate in the toolpath or process setup. If the error varies from part to part, compensation doesn’t work.

- Quality control becomes manageable: Repeatable output reduces inspection burden, scrap, and “mystery failures” during assembly.

- Tool wear and drift show up as changes in repeatability: A gradual decline in repeatability is an early warning signal—often indicating blade dulling, underlay wear, vacuum leaks, or rail/bearing issues.

- How repeatability can look “good” while accuracy looks “bad.”

- It’s common for a cutter to be very consistent (high repeatability) but slightly offset from nominal (lower absolute accuracy). In practical terms, that machine may outperform a machine that hits nominal occasionally but varies with speed, corners, and material lot.

- What to Look for Beyond the Number

- Repeatability claims only matter if they remain true under real conditions:

- After hours of cutting (thermal drift and wear)

- Across the entire bed (not just near the home position)

- At production speeds (not just slow demo speeds)

- On your typical material types (porous vs non-porous, thick vs thin)

The “Big Format” Reality

Large-format oscillating knife cutters (wide beds, long travel, high throughput) face real-world precision challenges that spec sheets often smooth over. Accuracy tends to be easiest near the center of travel at moderate speed. The farther you go, and the faster you move, the more the “big format reality” shows up.

- Why Big Format Makes Precision Harder

- Cumulative error across long travel: Tiny deviations per meter add up. What is negligible over 200 mm becomes significant over 2,000–3,000 mm.

- Structural deflection: Longer gantries and wider spans can flex more under acceleration and tool load, affecting corner fidelity and small-feature accuracy at speed.

- Drive system effects scale with length:

- Belts can stretch slightly and behave differently depending on tension and load.

- Rack & pinion systems can show backlash or pitch error if not well-tuned.

- Even with good components, maintaining uniform performance over long runs requires careful alignment and maintenance.

- Thermal expansion: Over a large frame, temperature changes can cause measurable dimensional drift. In some environments, the machine can “grow” slightly during a long shift.

- Vacuum and bed uniformity issues: Bigger beds mean more opportunity for uneven suction, clogged zones, underlay wear differences, and local flatness problems—each of which can create location-dependent accuracy variation.

- How to sanity-check large-format specs

- Ask whether the stated accuracy applies over the full travel or only locally.

- Request test results that include long straight cuts, large rectangles, and features placed in different bed locations (corners and edges, not just the center).

- Consider whether your jobs require tight tolerances across the whole sheet or only in localized regions. Big-format machines can be excellent, but expectations must match the physics and the maintenance discipline.

Precision Measurement

Separate Machine Motion Tests from Cutting Process Tests

Machine Motion Tests

These tests evaluate the mechanical and control accuracy of the axes without involving the blade or material. Typical approaches include:

- Commanding the machine to move to known positions and measuring the carriage location with a dial indicator, laser measurement system, or linear scale.

- Repeating moves back and forth to the same coordinate to assess repeatability and backlash.

- Measuring accuracy at different locations across the table to identify position-dependent errors.

- These tests establish a baseline for what the motion system is capable of under minimal load.

Cutting Process Tests

A Practical Cut Accuracy Test Pattern

An effective cut accuracy pattern typically includes:

- Large squares or rectangles to evaluate absolute dimensional accuracy over distance.

- Circles of multiple diameters to reveal blade offset issues, corner handling behavior, and path interpolation quality.

- Small holes and narrow slots to test the minimum feature size and detail fidelity.

- Sharp internal and external corners to assess corner rounding, acceleration effects, and blade tip limitations.

- Repeated features are placed in different bed locations to check consistency across the working area.

Measurement Tools and Uncertainty

Choosing the right measurement tools

- Digital calipers are convenient and suitable for millimeter-level checks, but their accuracy and user technique may not support tight tolerance claims.

- Micrometers provide higher resolution for thickness and small-feature measurements.

- Steel rules or tapes are useful for long dimensions but introduce greater uncertainty.

- Optical measurement systems or calibrated scanners can be effective for complex shapes, provided their accuracy is well understood.

Understanding measurement uncertainty

To reduce uncertainty:

- Use consistent measurement pressure and technique.

- Measure multiple samples and average results.

- Clearly define measurement points and methods.

- Avoid over-interpreting small differences that fall within measurement noise.

Common Precision Problems and Their Root Causes

Parts Come Out Consistently Undersized or Oversized

When every part measures the same amount off nominal, the issue is usually systematic rather than random.

- Common Root Causes

- Incorrect blade offset or tool compensation: If the effective cutting edge is not compensated correctly in software, all features shift inward or outward by a predictable amount.

- Material compression or elastic recovery: Soft foams and rubbers compress during cutting and rebound afterward, often producing parts that are slightly larger or smaller than expected.

- Incorrect scale or unit settings: File import errors (mm vs inches, DPI mismatches in print-to-cut workflows) can cause uniform size errors across the entire job.

- Consistent over-penetration into the underlay: Excessive depth increases drag and can push the cut line inward, particularly on small features.

- How To Diagnose

- If the offset is consistent across sizes and locations, cut a calibration shape (square or circle), measure it, and compare the deviation to the blade offset setting. If the error scales with feature size, suspect file scaling or material behavior.

Dimensions Vary from Part to Part

Variation between otherwise identical parts indicates instability rather than calibration error.

- Common Root Causes

- Inconsistent vacuum hold-down: Leakage, porous materials, or progressive loss of sealing as cuts accumulate can allow parts to shift differently from one cycle to the next.

- Blade wear over time: As a blade dulls, cutting force increases, changing material deformation and cut tracking.

- Material variability: Thickness, density, or stiffness variations within a sheet or between material batches can change how the blade interacts with the substrate.

- Thermal or mechanical drift: Long runs can introduce slight changes in machine behavior due to temperature, vibration, or wear.

- How To Diagnose

- Cut the same test pattern multiple times in the same location and then in different locations on the bed. If variation increases over time or across the sheet, investigate vacuum stability, underlay condition, and blade wear.

Corners Are Rounded or Distorted

Rounded or misshapen corners are among the most common complaints in oscillating knife cutting.

- Common Root Causes

- Aggressive acceleration and jerk settings: High corner speeds can force the controller to smooth paths, sacrificing corner fidelity.

- Blade tip geometry limitations: A blunt or thick blade cannot physically cut sharp internal corners.

- Material movement at direction changes: Corners concentrate forces, making them the first place where poorly held materials slip or deform.

- Incorrect corner strategy in CAM software: Some strategies intentionally round corners to maintain speed unless configured otherwise.

- How To Diagnose

- Slow down corner speeds and re-cut the same geometry. If corners improve significantly, motion tuning and cutting strategy are the likely culprits rather than mechanical accuracy.

Edges Are Fuzzy or Torn (Textiles, Felt)

Poor edge quality is often mistaken for dimensional inaccuracy, but it is usually a blade–material interaction issue.

- Common Root Causes

- Dull or inappropriate blade type: Worn edges pull fibers instead of slicing them cleanly.

- Insufficient oscillation frequency or amplitude: Low oscillation allows the blade to drag rather than cut.

- Excessive cutting speed: High feed rates increase tearing, especially in fibrous materials.

- Inadequate underlay support: Fibers can flex downward instead of being cleanly severed.

- How To Diagnose

- Inspect the blade under magnification and test a fresh blade with adjusted oscillation settings. If edge quality improves without changing geometry, the issue is cutting mechanics, not positioning accuracy.

Incomplete Cut-Through or Inconsistent Depth

Cuts that don’t fully separate or vary in depth undermine both precision and productivity.

- Common Root Causes

- Material thickness variation: Foams, felts, and laminates often vary across the sheet.

- Worn or uneven underlay: Grooves and compressed areas change the effective cutting depth locally.

- Incorrect tool pressure or Z-depth setting: Too shallow leads to incomplete cuts; too deep increases drag and distortion.

- Vacuum lift during cutting: Material lifting changes the reference plane, reducing effective penetration.

- How To Diagnose

- Check cut-through quality across different bed locations and rotate the material if possible. If failures follow bed position rather than part geometry, investigate the underlay condition and vacuum consistency.

Design for Precision

Use Realistic Corner Radii

One of the most common design-for-precision mistakes is specifying perfectly sharp internal corners when the cutting tool physically cannot produce them.

- Why Corner Radii Matter

- An oscillating knife has a finite blade thickness and tip geometry. Even the sharpest blade produces a minimum achievable inside radius.

- Forcing the cutter to approximate a zero-radius corner results in corner rounding, overcutting, or small “hooks” where the blade transitions direction.

- Tight corners amplify acceleration, jerk, and blade lag effects, making them the first place precision problems appear.

- Design Best Practices

- Specify an internal corner radius that is equal to or slightly larger than the blade’s effective cutting radius.

- Use consistent radii across the design to improve predictability and toolpath stability.

- For mating parts, ensure both sides share compatible radii to avoid fit issues.

Avoid Ultra-Thin Features in Stretchy Materials

Stretchy and compressible materials such as textiles, rubber, vinyl, foam, and felt place practical limits on how thin a feature can be while remaining dimensionally stable.

- Why Ultra-Thin Features Fail

- Narrow bridges, tabs, and walls stretch or compress under blade pressure.

- As cutting progresses, thin features lose surrounding support and become more likely to distort or tear.

- Even if the machine cuts them “correctly,” elastic recovery after cutting can change final dimensions.

- Design Best Practices

- Increase minimum feature width beyond what looks acceptable on screen—especially in soft or elastic materials.

- Use gradual transitions instead of abrupt, narrow sections to reduce stress concentration.

- When thin features are unavoidable, plan for reduced cutting speed and enhanced hold-down.

Add “Holding Tabs” Where Appropriate

Holding tabs (also called bridges) are small uncut sections that keep parts attached to the main sheet until cutting is complete.

- Why Holding Tabs Improves Precision

- Once a part is fully cut free, vacuum sealing weakens, and the part can shift or rotate.

- Internal features cut after the outer contour may lose accuracy if the part moves even slightly.

- Tabs maintain positional stability throughout the cutting process, preserving feature alignment.

- Design Best Practices

- Place tabs in non-critical areas where small cleanup marks are acceptable.

- Use enough tabs to prevent movement, but not so many that removal damages the part.

- Adjust tab size and count based on material stiffness and part size.

Keep Grain/Flute Direction Consistent

Many materials used with oscillating knife cutting machines are directionally sensitive. Corrugated board has flutes, textiles have grain, and some plastics have extrusion direction.

- Why Direction Matters

- Cutting parallel vs perpendicular to the grain or flute changes cutting resistance and deformation.

- Dimensional accuracy and edge quality can vary depending on orientation.

- Mixed orientations within a nest can produce inconsistent results across parts.

- Design and Nesting Best Practices

- Align critical features consistently relative to grain or flute direction.

- Nest parts with similar orientation to maintain uniform cutting behavior.

- Consider grain direction during part layout, not as an afterthought.

Maintenance and Calibration

Daily and Weekly Checks

Routine checks are the first line of defense against precision loss. These tasks are simple, fast, and often reveal issues before they become serious.

- Daily Checks

- Clean the Cutting Bed and Vacuum Zones: Dust, fibers, and small offcuts reduce vacuum efficiency and create uneven hold-down, leading to micro-movement during cutting.

- Inspect the Blade Condition: Look for visible dulling, nicks, adhesive buildup, or fiber wrapping. Even slight blade degradation increases cutting force and distorts precision.

- Verify Vacuum Performance: Listen for changes in pump sound, check for zones that feel weak, and ensure unused zones are masked or closed.

- Check Tool Holder Security: A loose blade or tool holder introduces play that shows up as inconsistent feature accuracy.

- Weekly Checks

- Inspect Linear Rails and Bearings: Look for debris accumulation, dry spots, or unusual noise during motion.

- Check Belts, Racks, or Couplings: Early signs of wear, looseness, or contamination often appear before accuracy visibly degrades.

- Review Underlay Condition: Grooves, compression, or embedded debris change depth, consistency, and feature support.

- Run a Quick Test Cut: A small reference pattern can reveal drift in size, corner quality, or edge finish before production parts are affected.

Periodic Calibration

Key calibration areas:

- Axis Squareness and Alignment: Over time, vibration and thermal cycling can cause small shifts that affect rectangular accuracy and diagonal measurements.

- Home Position and Limit References: Drift in home sensors or switches changes the reference for all subsequent moves.

- Tool Offset and Blade Calibration: Blade changes, tool holder wear, or slight misalignment can alter the effective cutting position.

- Vision System Calibration (If Used): Camera-to-tool offsets, lens distortion correction, and lighting conditions must be verified to maintain registration accuracy.

- Z-Axis Depth Reference: Underlay wear and mechanical settling can change effective cutting depth even if Z values haven’t been altered.

Blade Management as Controlled Variables

Blades are consumables, but they are also precision tools. Treating blade condition as a controlled variable rather than an afterthought is one of the most effective ways to preserve accuracy over time.

- Why Blade Management Matters

- Cutting Force Increases as Blades Dull: Higher force leads to more material compression, stretch, and blade deflection.

- Edge Quality Degrades Before Dimensions Fail: Fuzzy edges, tearing, or rough corners often appear first, serving as early warning signs.

- Repeatability Suffers: As blade condition changes, the same settings no longer produce the same results.

- Best Practices

- Track blade usage by material type and cutting distance or time.

- Replace blades proactively rather than waiting for visible failure.

- Standardize blade types for specific materials and document proven settings.

- Clean adhesive or resin buildup regularly to maintain consistent cutting behavior.

Oscillating Knife Precision VS Other Cutting Technologies

Versus Laser Cutting

Versus CNC Routing

Versus Die Cutting

Versus Waterjet Cutting

What Actually Determines Precision Most in the Real World

Material Behavior and Stability

Key influences include:

- Elastic recovery in textiles, rubber, and vinyl

- Compression and rebound in foams, felts, and gaskets

- Internal structure in corrugated and honeycomb materials

- Thickness and density variation across a sheet

Vacuum Hold-Down, Fixturing, and Flatness

High-impact factors include:

- Vacuum zone design and leakage control

- Material contact quality with the bed

- Loss of suction as cut-through paths open

- Underlay condition and uniform support

Blade Condition, Geometry, and Oscillation Settings

The blade is where precision becomes physical. Blade-related variables strongly affect feature fidelity and consistency:

- Tip geometry defines the minimum achievable corner radius

- Blade offset and compensation determine systematic size accuracy

- Oscillation frequency and amplitude control cutting force and drag

- Blade sharpness governs material deformation and repeatability

Cutting Strategy and Motion Dynamics

Major contributors include:

- Acceleration and jerk settings at corners

- Inside-out vs outside-in cutting order

- Use of tabs to maintain part stability

- Multi-pass cutting for thick or tough materials

- Depth and pressure control consistency

Registration Workflow and Distortion Compensation

Critical elements include:

- Material loading consistency and squareness

- Vision system accuracy and calibration

- Fiducial design and placement

- Compensation for print or material distortion

Machine Structural Design and Motion Hardware

Important aspects include:

- Frame and gantry stiffness

- Linear guide quality and alignment

- Drive system choice and tuning

- Encoder resolution and feedback architecture

Maintenance, Calibration, and Environmental Stability

Influences include:

- Rail contamination and wear

- Underlay degradation

- Thermal drift in large-format machines

- Loss of calibration in vision or tool offsets

CAD Design and Nesting Choices

Examples include:

- Unrealistic zero-radius corners

- Ultra-thin features in elastic materials

- Inconsistent grain or flute orientation

- Lack of holding tabs for small parts

How to Choose Machines When Precision Is The Priority

Ask for Real Cut Samples of Your Material

Nothing predicts precision better than seeing how a machine cuts your material under realistic conditions.

- Why Samples Matter

- Different materials respond very differently to oscillating knife cutting. A machine that looks perfect on vinyl may struggle with thick foam, dense rubber, or fibrous textiles.

- Material thickness, density, surface friction, and internal structure all influence dimensional accuracy and edge quality.

- Demo samples often use ideal settings, fresh blades, and slow speeds—conditions that may not match production reality.

- What To Request

- Cut samples using your actual material or an exact equivalent, not a “close substitute.”

- Include features that matter to you: small holes, tight corners, long straight runs, thin bridges, and mating edges.

- Ask for samples cut at realistic production speeds, not just slow, showroom-quality settings.

- Request multiple samples from different bed locations to assess consistency across the work area.

Look for Robust Toolhead and Tangential Capability if Needed

The toolhead is where theoretical machine accuracy becomes physical cutting performance.

- Why Toolhead Design Matters

- A rigid toolhead resists vibration and blade deflection during rapid direction changes.

- Poor toolhead stiffness or sloppy blade retention directly degrades corner fidelity and repeatability.

- Controlled oscillation mechanisms produce cleaner edges and more predictable cutting forces.

- Tangential vs Non-Tangential Knives

- Tangential toolheads actively rotate the blade to align with the cutting direction. This improves corner sharpness, reduces drag, and enhances accuracy on thick, dense, or high-friction materials.

- Non-tangential knives rely on passive blade rotation. They can be very effective for many materials, but may struggle with tight internal corners or demanding tolerance requirements.

Evaluate Vacuum System Design, Not Just Pump Power

Vacuum hold-down is one of the most underestimated contributors to precision.

- Why Pump Power Alone is Misleading

- A powerful pump is useless if suction is spread over too large an area or lost through leakage.

- Poor zone sealing, worn gaskets, or inadequate airflow distribution can undermine even the largest pump.

- What To Evaluate Instead

- Vacuum zone layout and the ability to activate only the zones in use.

- Seal quality and bed flatness across the entire working area.

- Performance with porous materials and partially cut sheets.

- Underlay compatibility and ease of maintenance.

Consider Workflow and Software

Precision is as much about control as it is about mechanics.

- Software Capabilities That Support Precision

- Reliable blade offset and tool compensation management.

- Advanced corner strategies and speed control by feature size.

- Inside-out cutting options and tab/bridge management.

- Multi-pass cutting support with consistent depth control.

- Vision-based registration and distortion compensation, if print alignment matters.

- Workflow Considerations

- Ease of calibration and verification routines.

- Clear feedback when parameters are out of range.

- Repeatable setup procedures that reduce operator variability.

Practical Setup Tips to Maximize Precision Immediately

Start With Flats, Stable Material Load

Precision begins with how the material is placed on the table.

- Allow rolled materials to relax before cutting to reduce curl and internal stress.

- Align the sheet squarely to the bed using guides or reference edges rather than relying on visual alignment.

- Ensure full contact between the material and the bed before activating the vacuum; trapped air pockets reduce holding force.

- For problematic materials, lightly pre-seat the sheet by activating the vacuum gradually or repositioning it once suction is applied.

Optimize Vacuum Zones and Seal Unused Areas

Maximize holding force where it matters.

- Activate only the vacuum zones that are covered by the material.

- Mask or block unused areas of the bed to prevent air leakage.

- For porous materials, use smaller active zones to concentrate suction.

- Pay special attention to late-stage cuts, when cut-through paths reduce sealing effectiveness.

Use a Sharp, Appropriate Blade and Verify Tool Setup

Blade condition is one of the fastest ways to gain or lose precision.

- Install a fresh blade when tight tolerances are required, even if the old blade “still cuts.”

- Verify blade type, tip geometry, and oscillation compatibility with the material.

- Ensure the blade is seated correctly and the tool holder is rigidly secured.

- Clean adhesive or fiber buildup from blades and holders before critical jobs.

Set Conservative Depth and Pressure First

More force rarely improves accuracy.

- Use the minimum depth and pressure needed to achieve a clean cut-through.

- Avoid excessive over-penetration into the underlay, which increases drag and dimensional shift.

- Verify depth consistency across the bed, especially if the underlay shows wear patterns.

Slow Down Where Precision Matters Most

Uniform speed is not always optimal.

- Reduce speed in tight corners, small holes, and narrow features.

- Allow the machine to run faster on long, straight edges where forces are more stable.

- Avoid aggressive acceleration and jerk settings for intricate geometry.

Cut Inside Features First and Use Tabs When Needed

Sequencing affects stability.

- Cut internal features while the sheet is still fully supported.

- Add holding tabs to keep small or flexible parts anchored until the end.

- Remove tabs cleanly after cutting rather than risking part movement during the job.

Run a Quick Verification Cut

Before committing to full production:

- Cut a small test pattern that includes critical features.

- Measure it using a consistent method and confirm fit or alignment.

- Adjust compensation or settings once, rather than correcting after a full run.